“I still want people to understand that it was one of the best jobs in the world, rather than looking back and moping.”

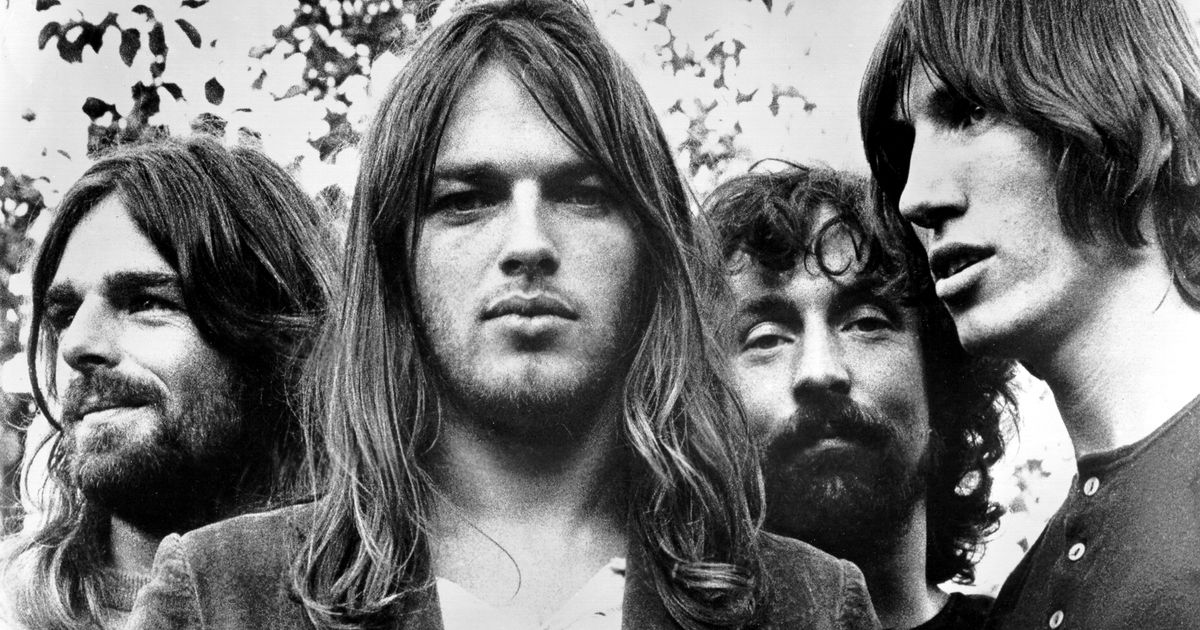

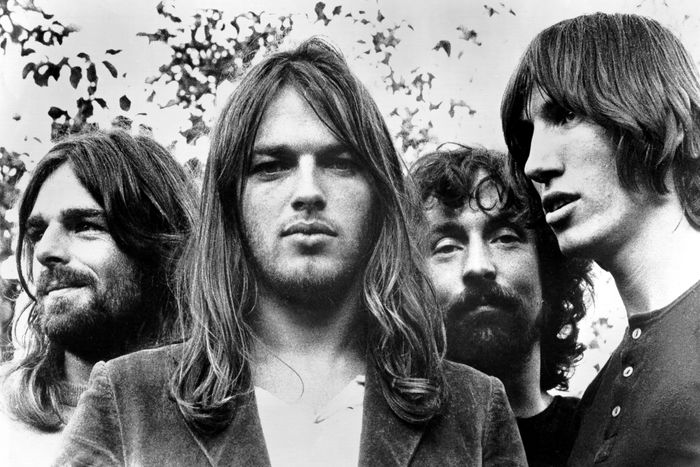

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Recently, one of Nick Mason’s daughters persuaded him to do an online Pink Floyd quiz, just for the hell of it. “I scored 56 percent,” he admits with a chuckle. “I do remember feeling it was rather pathetic.”

The drummer, now 81 years old, doesn’t let his somewhat lapsed memory deter him from serving as the band’s chipper envoy for their reissued projects of late, which has included Live at Pompeii in Imax and an anniversary remastering of The Dark Side of the Moon. Five decades later, Mason gets to do the same for their masterpiece about absence: Wish You Were Here. Released in September 1975, the album’s sedulous world-building broke ground after an unexpected studio visit from co-founder Syd Barrett, who had departed Pink Floyd several years earlier on account of mental-health concerns. “Shine On You Crazy Diamond,” a gorgeous eulogy of a composition that serves as Wish You Were Here’s bookends, was created in his memory, while “Welcome to the Machine,” “Have a Cigar,” and “Wish You Were Here” have all become era-defining tracks that probe the unscrupulous music industry. There’s no reason to try to offer a dissenting view: David Gilmour, Roger Waters, Richard Wright, and Mason recorded one of the greatest albums in the rock canon, bar none.

Wish You Were Here 50 features six recordings that have gone unreleased until now, including a demo of what was ultimately turned into “Welcome to the Machine.” And if you want to further connect the art to the masses, there are 25 bonus tracks to cue up. As for why Mason — Pink Floyd’s sole continuing member from start to finish — continues to enjoy communicating the band’s history in a way that his peers often don’t, his answer is twofold. “It’s partly because I’m proud of what we did and partly because we have a reputation for arguments,” he explains. “But the reality was we had a lot of very happy times together. I loved all of the touring we did and all the time we spent in the studio. It was a wonderful way to spend a life. I still want people to understand that it was one of the best jobs in the world, rather than looking back and moping.”

David Gilmour has stated that this is his favorite Pink Floyd album. Where does it rank for you personally?

It’s probably a favorite for all of us, because it’s got so much air around it after Dark Side of the Moon. It’s a feeling that this is the antithesis of that sort of music. We’re not worrying about the structure of it, in a way. It’s almost playing itself through.

What air were you breathing in?

It’s a very curious period for us because we’ve been a proper band touring America for the first time and seeing success. But by the time we hit Wish You Were Here, we’re beginning to get a little bit older. Some of us had kids by then. The trouble with the music industry is it’s not very good for growing up. We’re not growing up very much, but we are getting older and hopefully a little bit wiser.

When you all gathered to record Wish You Were Here, you were in this unique psychological position of coming off The Dark Side of the Moon — a monolith of success and acclaim. What was the attitude like among you all during those first few weeks of recording, and how did that reflect your drumming?

The first few weeks of recording after Dark Side was the project known as Household Objects, and that sort of went nowhere. We had to more or less let it drift away and really start again. There was very little from that album concept that went forward from there. As far as I remember, we spent a lot of studio time waiting for something to happen or something to kick us off. And then there was this very odd thing of Syd Barrett appearing one day. All of us seem to have slightly different versions of when he was there, and whether he was there for one day or two days, and so on.

Yeah, there seems to be a decent amount of conflicting stories about Syd’s visit. Can you tell me what you remember about his presence and how it affected you?

I’m sure he was there for two days because one of our crew members had taken some pictures, and his wardrobe is different in half of them. What I remember was that first occasion: He wandered into the control room, I followed in a bit later, and I simply didn’t recognize him. It was shocking, really, because I have a very clear memory of Syd when I first met him. He was a very bright, very chirpy character. And here was this large, overweight guy with very little hair. I don’t think anyone knows why he decided to come to Abbey Road or how he would know we were there. “Confusion” is the word I would use to describe the effect it had on me. It took until David actually asked, “Do you know who that is?” to enable me to begin to understand. His visit was the catalyst that the record needed to get going.

Did you ever try to contact him in the ensuing years prior to his death?

No. It was generally accepted that he should be left alone. That’s what the family certainly suggested, and we felt we should respect that. Now, whether that really was the right thing or whether we should have maybe pushed a bit harder. But from that point of view, we probably aided and abetted the idea of leaving him alone. Occasionally, people would work out where he lived and go and bang on the door. We felt that should be stopped and prevented.

Do you regret not pushing to see him?

Not really. It’s more like the mind sort of wonders. Frankly, what’s more important was when Syd left the band in 1968. Maybe we should have done more. But we didn’t know any better.

Were there any other catalysts besides his visit that got things moving?

It was almost certainly Rick playing around on the keyboards and the use of guitars being played through a Leslie speaker, which was a rather odd way of making different sounds. See, the trouble with 50-odd years in this band is you simply don’t remember what really happened. I’m quite fond of saying that. I think there’s never quite enough credit to go around. There’s always a shortage somewhere. I don’t think I’ve suffered particularly from that.

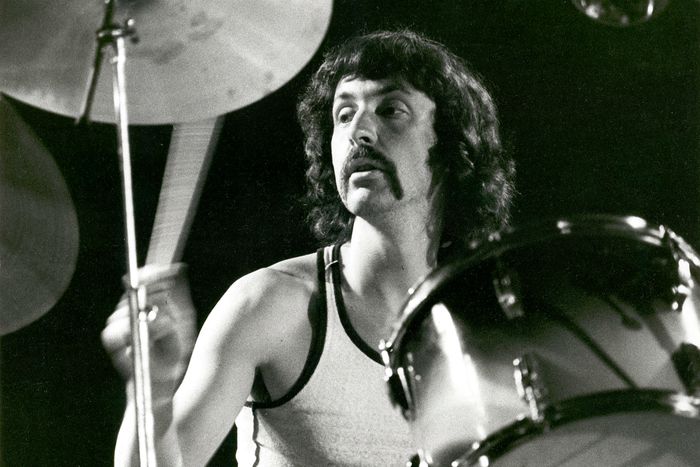

“I don’t think we lost faith in what we could do. It was more about finding that one thing to kick everything else off.”

Photo: Christian Rose/Roger Viollet via Getty Images

Well, did you at all lose faith in your abilities?

No, I don’t think we lost faith in what we could do. It was more about finding that one thing to kick everything else off. That goes through all sorts of creative endeavors. It’s easier at the beginning than when you’re following on. And certainly after you’ve had a really successful record, whatever you do, you don’t want to do the “part two” and repeat yourself. It’s very difficult to find something else. That’s a good starting point, I think. The good thing about Household Objects was the fact we were so relieved when we shelved it. It’s sort of absurd now in the 21st century because, well, even 20 or 30 years ago, once you’ve got the electronics, you can use all sorts of sounds and make them do anything you want. We could have made Household Objects in an afternoon in the present day.

By my understanding, you felt that you all could’ve drawn things out a bit longer in the studio for this album.

It’s funny, I’ve not thought about this before: Of course when we were working on Dark Side, it was pretty linear in terms of knowing there were various components, but it was then fairly easy to link them up and work out roughly how they should be. When I look back on Dark Side, I sometimes think that, well, the running order is fine, but it doesn’t work particularly well live. We possibly should have modified it somewhere along the line. There was much more of a sense that things could be accomplished in an afternoon or in a day; I don’t think anything took more than a month to do. With Wish You Were Here, I have no recollection of the way we ordered it; what I’m still really conscious of is the fact that we took a long time to do it. Maybe too much time.

Between “Welcome to the Machine” and “Have a Cigar,” there’s a unified theme of being frustrated by the greed and insincerity of the music industry. Even with your ethics, what were the biggest temptations you contended with around Wish You Were Here?

The main thing would be the way the live shows suddenly accelerated from being in theaters to stadiums and the attempt to go “bigger.” The fact is, most music benefits from being in the theater rather than the stadium. There’s something quite nice about having 90,000 of your own tribe approve of what you’re doing, but with the big festivals and so on, it’s not quite as good as a live theater audience. We tried quite hard to find ways of breaking that down a bit with inflatables and movie footage and so on — we did move on from just having cameras on the band members. But if you’ve got a full theater, that’s it. If you’ve got a full stadium, 70 percent are there for the music, and 30 percent are somewhere around the back doing drugs and throwing frisbees, so you’ve lost some of them. Maybe it’s okay if it’s at a frisbee festival, but not for Pink Floyd.

Did your reality end up aligning with what those themes magnified? Not just with ever-present industry battles, I suppose, but also the idea of aging as a rock musician and how graceful you can choose to make it.

It’s sort of bizarre the way we were there. It was initially assumed that any band would last for about a year to two years, maximum. Even the Beatles were living on borrowed time. I remember Ringo Starr talking about opening a chain of hairdressers. I don’t think any of us foresaw the way that we could still be here, pottering about, 50 years later. But we didn’t think about it that much. You’re always thinking about the next step, not the next steps. It was always like, What do we do next? It’s a bit of touring and then the next record.

Do you feel like the band was generally well managed throughout its lifespan?

Yeah, I think we were. We owe a huge debt of gratitude to the Beatles, who changed the attitude of record companies in terms of respecting bands. It used to be that they would allocate two recording sessions for the making of a single song. But, 15 years later, you’d have a lockout on studio two at Abbey Road for as long as you needed it. In general, we had people who represented us who did best they could in an industry that’s often weighted against the musicians. It’s easy to attack the record companies, but over the years, there’s been a lot of very good people working there. We owe quite a lot to some of the record-company personnel.

I know Roger and David disagree on the resonance of Roy Harper singing the lead vocals on “Have a Cigar.” Where do you stand on his contributions?

I think he did a great job. When we couldn’t decide on something, if we could find a third route, that’s a good thing. It’s a little bit like Chris Thomas doing the mix on Dark Side — rather than end up wasting hours arguing about it, it’s far better to get on. I thought it was a nice idea having Roy sing it. He’s got a slightly gravelly thing going on, which neither David nor Roger quite have. Yeah, it was a good choice.

Did you ever consider volunteering your own vocals for the occasion?

No, I didn’t. It’s not something that would’ve appealed to me. I’ve always been happiest on my riser with my drum kit.

I know people tend to buzz around the “Oh, by the way, which one’s Pink?” line, but I’ve always loved the bite of “You gotta get an album out, you owe it to the people.” What do you feel Pink Floyd owed to its fans at the time of Wish You Were Here?

We didn’t feel like we owed anything to the fans in that way, because what matters is what we were actually producing. The fact that fans want to buy more records is a good driver for that. You want to spend the time, but you have to please yourself first. There aren’t many people who can second-guess what the audience might like and then record accordingly. You have to make sure that you’re proud of it, bite the bullet, and play it to the fans, and then see if they like it or not. You waste time if you start trying to guess what other people will like.

I mean, you do want approval and you want to be successful. There’s an element of competition and wanting success, but you achieve it by doing what you think is right and good as opposed to being driven by the fans or the record company. The record companies left us alone and let us get on with it. I just don’t think there’s anything healthy in who can sell the most tickets. It wasn’t really a competition with “Who’s No. 1?” When we were touring, we were almost unaware of what was going on in the rest of the world. Someone would come up and say the album’s No. 1. We’d be like, Well, that’s great, but it’s sort of secondary to the actual business of playing the gig.

Do you see yourself as a mediator between Roger and David now? How’s your relationship with both of them given their very public tiff?

I’m hopefully friends with both, but I don’t necessarily see myself as a mediator. I’m not Henry Kissinger. I’m more of the Neville Chamberlain of our band. But for Roger and David, there’s no future for them.

Several years ago, you and Stewart Copeland appeared on an episode of The Grand Tour to determine the “fastest drummer from a band beginning with the letter P.” You two hadn’t met each other prior to filming the segment. Are there any other drummers who, for whatever reason, you’ve still never crossed paths with and would like to?

It’s a curious industry in a way, because you spent an awful lot of time playing the gig the week after someone else was there playing their gig. It’s socially limiting unless you’re all doing festivals together. There’s all sorts of people who I’ve never come across, but it’s generally terrific when I do finally meet them. Stewart and I had dinner together the night before we filmed that segment, and funny enough, I went to see him about a month ago because he was in the U.K. doing a few engagements.

Drummers always have stories that resonate from one to another. My favorite was I was once out to dinner several years ago with about ten really well-known drummers, all of whom I have enormous respect for and admire. For some reason, we got onto the subject of Van Morrison. One of them said, “Hands up everyone who’s been fired by Van Morrison!” And nine out of ten put their hands up into the air. The only time I played with him, I wasn’t being paid, so he couldn’t fire me. Things like that definitely bring you together to the brotherhood.