“All he told me was ‘I wrote something for you. I’m not an idiot. I said ‘yes.’”

Photo: Jai Odell for New York Magazine

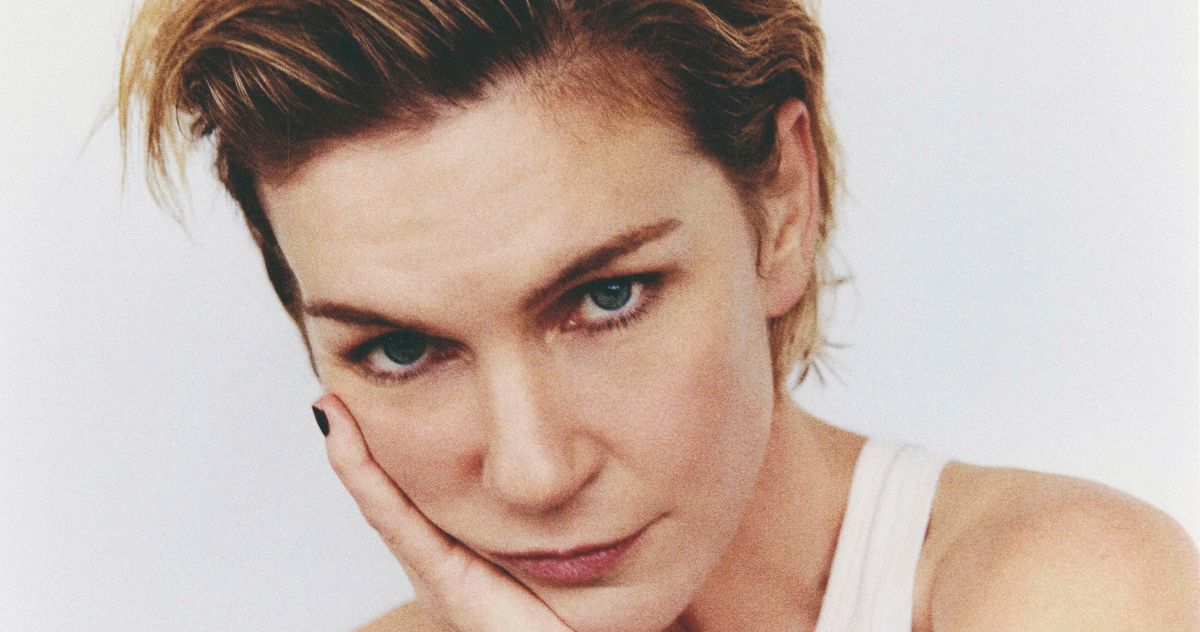

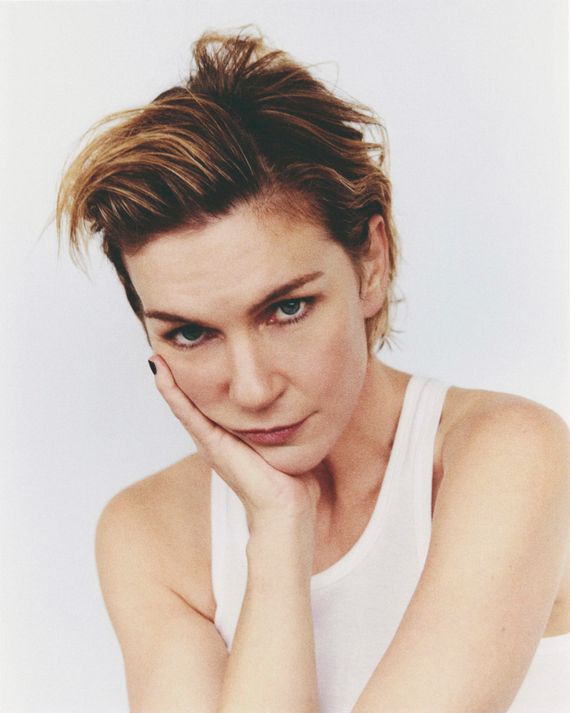

Rhea Seehorn has a thing for libraries. As she arrives for our interview at the Philosophical Research Society, a New Agey outfit in a Mayan Revival building in Los Feliz, she tells me she’s excited to discover a new library right here in Los Angeles, where she lives. Seehorn, 53 — Rhea is her middle name, pronounced “Ray” — has dusty-blonde hair and an athletic, forceful presence. Having just come from the Wrap’s Power Women Summit, she arrives in a businesslike blazer and a full face of makeup, which sharpens her features. She apologizes for her extravagant appearance, then returns to nerdy enthusiasm for her surroundings, suggesting I follow the Instagram account @1000libraries, which features venues like this. We get a tour from an attendant, learning that the place was built around a collection of esoterica by Manly P. Hall, a man who had the very early-20th-century idea of merging many faiths into a cohesive whole.

“I’m sure Vince will want to know about this,” she tells me, referring to Pluribus creator Vince Gilligan. We’re here on a day when the building is closed to other visitors, which makes it eerily quiet, as if some semi-mystical force has intruded on normal life and left us alone in the universe. They’re just the right conditions to discuss a show in which, owing to a potentially extraterrestrial message from the stars, nearly everyone in humanity gets combined into a hive mind — with the exception of Seehorn’s character, Carol, who finds herself alone in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and a few individuals scattered across the globe. The members of the hive, often represented in their conversations with Carol by an emissary played by the ominously serene Karolina Wydra, are all very happy to share in one peaceful, collaborative utopia on earth. So, too, are the remaining un-“joined” humans, who are enjoying serenity with the hive at their beck and call. Carol, a miserable romance writer, absolutely hates them for it and, both intentionally and accidentally, sabotages their project, insisting that everyone else has no idea what’s right for them. The show progresses in a series of sci-fi twists that have been fodder for the 2025 equivalent of watercooler conversation.

It’s Seehorn who grounds the series in real and prickly human emotion. Gilligan and his writing staff construct extended sequences for Carol, whether her activities are mundane, like getting drunk and watching The Golden Girls, or grueling, like trying to bury the body of her wife, Helen. Seehorn tells me she maps out every beat. When Carol’s falling asleep watching a sitcom, Seehorn’s thinking about why Carol’s not sleeping in her own bed, what would be going through her mind as she wakes up, how it reflects her relationship to her current waking nightmare. Carol’s feelings are a stew of grief, resentment, terror, and self-righteousness, all of which flicker — briefly but legibly — at rapid speed across Seehorn’s face and physical bearing in any given scene. “It’s a great gift to act on the emotions rather than say them out loud,” Seehorn tells me. “Sometimes without even having to make the audience specifically sure of what I’m thinking.” The performance has already earned her a Golden Globe nomination and inspired dozens of Reddit threads debating whether Carol’s attempts to undo the “joining” make her a monster.

In Pluribus.

Photo: Apple TV

Seehorn first worked with Gilligan on six seasons of Better Call Saul, which he co-created with Peter Gould. Her character, a prim lawyer with a perfect ponytail named Kim Wexler, was initially meant to provide Bob Odenkirk’s Jimmy, a character spun off from Breaking Bad, with someone to confide in. But Seehorn, working with the slight amount of dialogue she’d been given, found something intriguing in Kim’s reserve. “Not speaking can be a position of weakness, for sure, but it could also be a position of strength,” she says. After trying out a shot in the fourth episode in which Kim smiled, barely perceptibly, while watching Jimmy pull off a stunt, the creators settled into the idea that her character wasn’t a scold but was turned on by Jimmy’s shenanigans — and could be a surprising and active ally. From there, Kim’s role grew until she was something of a second protagonist. By the end of the series, Seehorn had been routinely hailed in the press as the show’s “MVP” or “secret weapon” and had racked up two Emmy nominations for Supporting Actress in a Drama Series.

The attention was new for Seehorn, who kept a low profile in her early career. Her father was in naval intelligence, and she moved around a lot growing up, eventually settling in Virginia. In college at George Mason University, she studied studio art but picked up an acting class as an elective and loved it. Thank God, she adds, it was “a technique-driven script-analysis class and not ‘Let’s talk about our feelings,’” which would have immediately lost her interest. After college, she pursued a stage career in the D.C. area, then in New York; the space Seehorn’s been given to experiment with her choices in Pluribus, she says, has felt very close to doing live theater.

In 2003, she landed a third-fiddle role in ABC’s I’m With Her as the sardonic sister to Teri Polo, whose schoolteacher character dates a famous actor. That series lasted a season, but it set Seehorn on a trajectory of playing comedic supporting roles. In an ensemble, Seehorn saw herself frequently performing something like a Bea Arthur part (one of her idols) — what she refers to as “being the tuba in the otherwise very high-note symphony.” Everyone around her is flitting about, “then I walk across the back of the stage going oompah-doompah, give a deadpan look, exit,” Seehorn says. It’s a quality you can see in Carol, too — another lonely tuba of a character who lives on her own little sitcommy artificial street in New Mexico but has no ensemble to bounce off.

Seehorn could feel her lane in Hollywood become increasingly constricted. She tells me she “would see dramas and think, Gosh, I could have gone in for that,” then discover that those shows’ producers weren’t interested in seeing her because she was known only for her multi-camera roles. She credits casting directors like Sharon Bialy, who eventually brought her in for Saul, for seeing past her most recent roles and retains a detached amusement about the way powerful people in Hollywood tend to do business. Four seasons into Saul, Seehorn went to audition for a comedy film. The casting director called her, laughing, and said the producers had asked for a tape of her being funny. Seehorn delivers the deadpan punch line: “So that was interesting.”

Photo: Jai Odell for New York Magazine

For Pluribus, Seehorn didn’t have to audition. Gilligan presented her with the concept for the series, which he’d been mulling over for about a decade, just after Saul wrapped its final season. “All he told me was ‘I wrote something for you,’” Seehorn says. “I’m not an idiot. I said ‘yes.’” Gilligan initially saw Pluribus with a male lead but so badly wanted to work with Seehorn again that he tailored the concept around her. “Halfway through the first season of Better Call Saul,” Gilligan says, “we were already thinking, How do we keep working with her when the show is over?” Pluribus reunites the creator and star with much of the crew that worked on Saul and even Breaking Bad and, like those shows, films mostly in Albuquerque. Still, Pluribus signals a remarkable shift in position for Seehorn, who is now, for the first time, the lead and face of a high-profile project. The actress is cautious in ascribing too much power to her position. “She had such a profound gratitude and awareness of the position she was in, and that isn’t always the case with the No. 1 on the call sheet, or any person with a certain amount of power,” Miriam Shor, who plays Carol’s late wife, Helen, tells me. “I marveled at it, because there’s an enormous amount of pressure on her.”

Seehorn sees it as part of her job to make sure everyone shows up prepared and respectful of one another’s work. She runs me through her immense appreciation for the various departments at work on Pluribus: “I’d like to think they know that I never think what I’m doing is more important than what they are doing.” She invests in welcoming the show’s guest stars — “It’s very difficult to come straight from a hotel room and jump onto a set where everybody knows each other,” she says. “I’ve been there” — and raves about her ensemble. When she describes how impressed she is with Wydra’s performance, Seehorn tells me she’s purposefully avoiding saying the word proud because she doesn’t think she should take credit for someone else’s work. “I always struggle with that word, if it’s okay to say about someone,” Seehorn says. “I think all scene partners make each other better,” she adds, “but she has her talent with or without me.” (When I relay that exchange to Wydra, she breaks into a big smile: “She was always meant to be a leading lady.”)

Given that we’re in a library, I suggest that Manly P. Hall might have bought some tomes on pride we could consult, maybe something Greek, though I insist it’s possible to be proud of something without taking responsibility for it. And as Seehorn finds herself in a position of authority on a set, her character is simultaneously thrust by fate into being the protagonist. There are many possible interpretations of the central metaphor of Pluribus — maybe it’s about capitalism versus communism, the experience of COVID lockdown, how much we value creativity as a society, veganism (the hive refuses to kill anything, but it does scavenge human remains), or how it’s evil to order DoorDash. Seehorn’s amused by the number of writers she’s talked to who, with the well-being of their own industry on their minds, see the show as a warning against artificial intelligence. The actress tends to read Carol’s actions as a manifestation of her overwhelming grief. She generally takes Carol’s side against the “joining” — but “not always in her behavior,” she says. In that hive mind, though so much suffering would be absolved, “there will never be surprise. There will never be a new book; there will never be a joke. You’ll never have childlike wonder again. It’s an easy decision, I think.”

Since Gilligan gave her the first script when they initially discussed the role, she has learned more about Carol episode by episode. It’s a method that resonates with her. “I’m assembling the jigsaw pieces that are known to me, supplying subtext, but leaving it open to finding whole new ideas on the day,” Seehorn says. “Every script, there’s another puzzle piece that needs to organically be a part of who she is.” The show has already been renewed for a second season, but Seehorn says with a glint in her eye that she has no idea what will happen next, palpably relieved that she doesn’t have to lie or worry about accidentally giving me a spoiler. “I can’t say I saw any of the stories coming,” she says, reflecting back on what’s transpired so far, “and yet they never feel like a trick.”