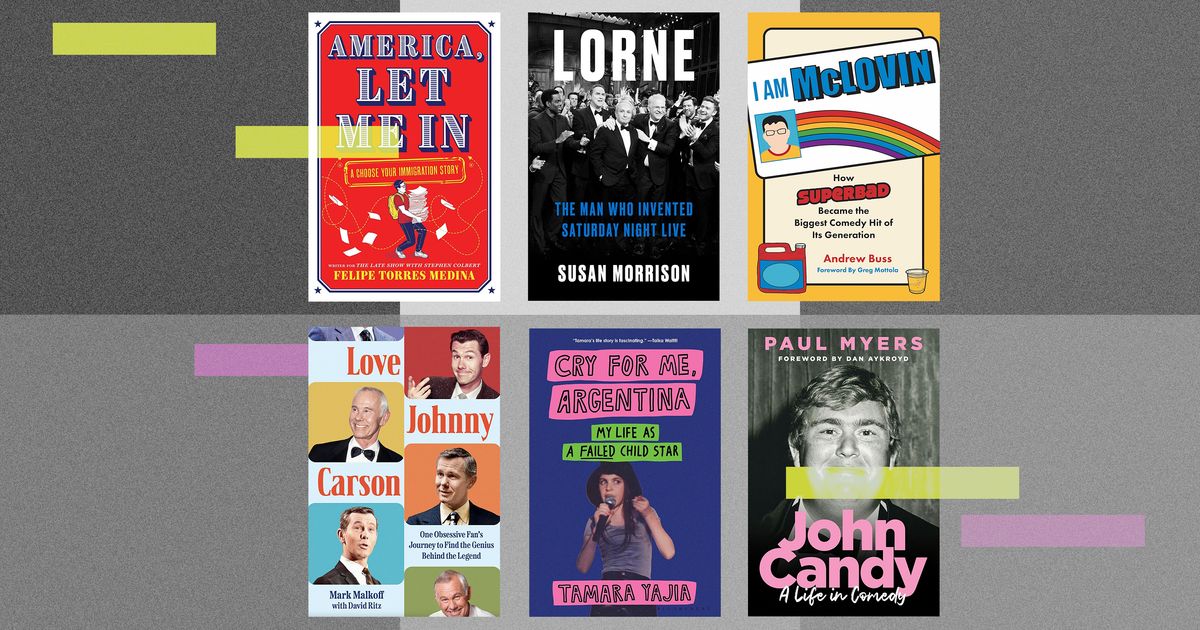

Photo-Illustration: Vulture

Mainstream comedy is frankly in a bit of a lull right now. Sitcoms and theatrical comedy movie are disappearing, few comic novels are getting published, and comedy podcasts are just comedians interviewing other comedians. It’s perhaps of little surprise, then, that the best nonfiction comedy books released in 2025 were focused on the past — comedy’s history, themes, and steadfast examples of greatness and insight.

Such books were all about asserting judgment. A little bit of nostalgia plays in too. How could it not? Comedy shapes us in our youth, and our youth shapes our comedic taste. But the goal of these books was mostly to assess or reassess largely overlooked cultural artifacts that acquired their legendary status over time. There are a few personal stories sprinkled in, but what ties them all together is a desire to reckon with history, to dig deeper and explore why some comedy mattered so much. At their best, they helped us understand the art form, and perhaps where it’s headed, a little bit more by showing us where it’s been. Here, then, are the ten best books about comedy that defined this year.

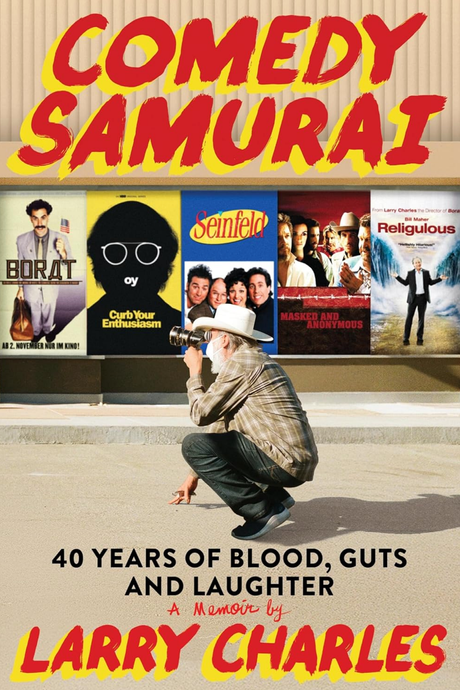

The way Larry Charles tells it, his role in creating some of the most pivotal comedies of the last several decades was accidental and back-doored. But even though the final product is invariably smooth and confident, all Charles’s projects — Seinfeld, Curb Your Enthusiasm, Borat — bear the unmistakable voice and imprint of their maker. In his professional memoir, Comedy Samurai, Charles seems to be his true self. He’s freewheeling while constantly trying to catch up with his own thoughts and daring impulses, a sensibility that informs his borderless and often experimental work. Comedy Samurai breezes by at a rapid clip; it’s confessional and disjointed, as if an old-timer were dictating his life story between drags of a cigarette.

Released in what’s now the distant year of 2007, Superbad might be the last great teen movie, or at least the millennial generation’s entry into that Hughes-esque canon of beloved films that capture the restless giddiness of being on the cusp of adulthood. Andrew Buss takes an adoring but critical eye to Superbad. He’s curious to find out everything he can about this modern classic while on his own quest that’s not unlike that of the film’s characters, except he pursues interviews and present-day takes instead of base teenage desires. His account is of an almost magical set where the comedy was organic and honest, emblematic of the aughts’ Apatow era of sensitive bro comedy.

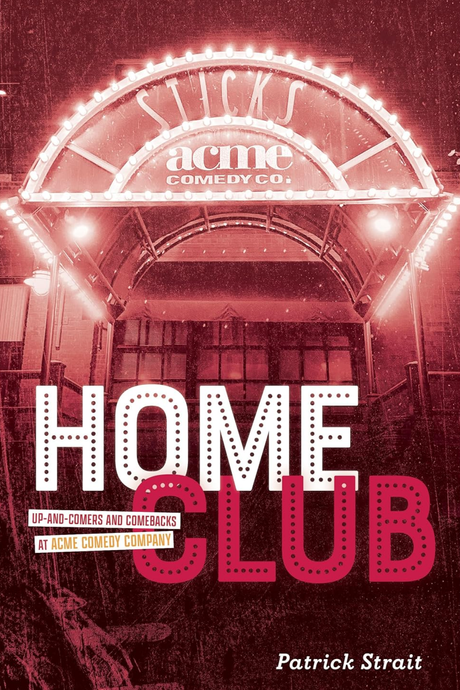

Much ink has been dedicated to the highs, lows, and impact of the 1980s stand-up-comedy-club boom. But what happened next? Well, the ’90s, obviously, an era when only the creative and scrappy clubs could survive and help generate another generation of comic stars. Minnesota comedy historian Patrick Strait delivers an absorbing history of Acme Comedy Company, the second-biggest club in Minneapolis during its peak era. Home Club is about the business of comedy without the luster and big-city glamour, providing a look into how such venues get started, operate, and somehow stay open for decades. There are plenty of stories in here about how Acme was an incubator for terrific mainstream and alt comics like Nick Swardson and Maria Bamford, but Home Club is at its most crucial when it’s also the story of Louis Lee, an emigrant from Hong Kong who makes Acme happen by grit and will, enduring booking wars, scene building, and economic disaster. It’s hard on every level to do comedy, not just on the creative side.

From Felipe Torres Medina, a staff writer on The Late Show With Stephen Colbert, comes this educational and eye-opening look at the quagmire of the immigration system. Medina, himself a survivor of what he depicts as a harrowing, arbitrary, and unfair game, surreptitiously tells his immigration story and lays out the hard facts the only way that it makes sense: as an interactive, choose-your-own-adventure-style puzzle read. America, Let Me In highlights the near impossibility of legally relocating to the United States by illustrating its tragically hilarious flaws and calling out the nonsense. If not for the deeply funny asides and anecdotes from the book’s fictional characters, the reader would be left enraged and shaking. America, Let Me In is cringe comedy of the highest order: There are serious stakes here.

Judd Apatow has been one of the biggest names in comedy for the past 30 years. He had a hand in The Larry Sanders Show and Freaks and Geeks before he made movies like The 40-Year-Old Virgin and Knocked Up. So a Judd Apatow Hollywood memoir would certainly be justified. Instead, the writer-director takes his trademark blend of delirious silliness and affecting emotion, applies it to himself, and gives us Comedy Nerd, a chronological autobiography and coffee-table book of consumption, history, and appreciation by one of the genre’s keenest minds. Real fans know this guy has been a comedy nerd since well before that term was in widespread use and now serves as that subculture’s patron saint. If you’re reading this, you’re probably a comedy nerd. And like Apatow, who shared everything he had, internal and external, braggy and embarrassing, for the joyous Comedy Nerd, you’ve got your own scars, relics, and mementos from a comedy life. This book is relatable and validating.

The many Saturday Night Live books out there treat Lorne Michaels delicately, following the lead of show alumni who harbor a mixture of fear of, intimidation by, and paternal love for the comedy kingmaker. Lorne is probably the first time his name hasn’t been uttered in hushed tones, because he’s not quite the inscrutable figure SNL nerds have been led to believe. Susan Morrison was granted heretofore unfathomable access to Michaels over a wide span of time; perhaps the perpetually Gotham-crazed subject trusted and was impressed by the author and editor because of her work at institutions like The New Yorker and Spy. She pulls down the manufactured myths and lore of Lorne to show us who he really is: a guy who, even in his postwar childhood in Canada, has always loved old-fashioned show business. According to Lorne, he’s not so much a comedy genius as he is a figure with a lot of drive, excellent taste, and a preternatural sense of what’s going to resonate with audiences. Lorne, then, is an observant and patient tale of the rise of a ruler who adapts and also thrives on chaos, Richard III meets The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes meets Animal House.

Author Christine Wenc wrote for the monumental and beloved satirical newspaper The Onion at the beginning of her non-fake journalism career, and she treats the subject with the seriousness it deserves. Part memoir, part exhaustive profile, Funny Because It’s True presents The Onion as a laser-focused satire and mirror of the American newspaper in its death throes. Beyond just recounting great Onion moments, Christine Wenc notes how the paper hipped us to the dangers of news as entertainment and the damage caused by toothless outlets like USA Today. There’s lots of history woven into the narrative, and Wenc makes a case for The Onion’s position in a long string of Wisconsin-based progressive newspapers, alt-weeklies, chaotic zines, and mythological tricksters. The Onion, the book posits, shows that college-style pranks can lead to real change while also earning comedians some cash; after all, the paper began as a way to sell ads.

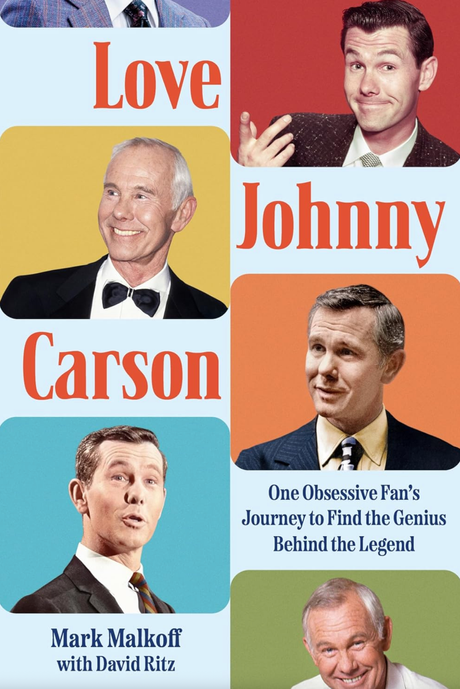

It’s subtly suggested throughout Love Johnny Carson that the king of late night is in danger of being forgotten. He’s been off The Tonight Show for more than 30 years now and dead for 20, so he’s definitely slipping into the past, threatening to turn into a plaid-jacketed straight man looking on amused in a collection of greatest-hits clips. Mark Malkoff isn’t going to let that happen. The lifelong Carson superfan (and podcaster on the subject) compiled an incisive and exhaustively detailed biography that breaks down the comedy figure deemed inscrutable in his lifetime by examining his work. Love Johnny Carson is about the late-night legend’s comedic impact, and while adoring, it isn’t hagiographic; it’s insistent that the man was all about the work. Malkoff busts myths instead of adding to them, discussing the little-known tales of how Carson was an unpopular choice to take over The Tonight Show and how NBC nearly dumped him early on. The book also runs down every familiar and unfamiliar Tonight Show highlight, giving readers the context of why they actually mattered at the time and how they showed off an agile and experimental comedy mind.

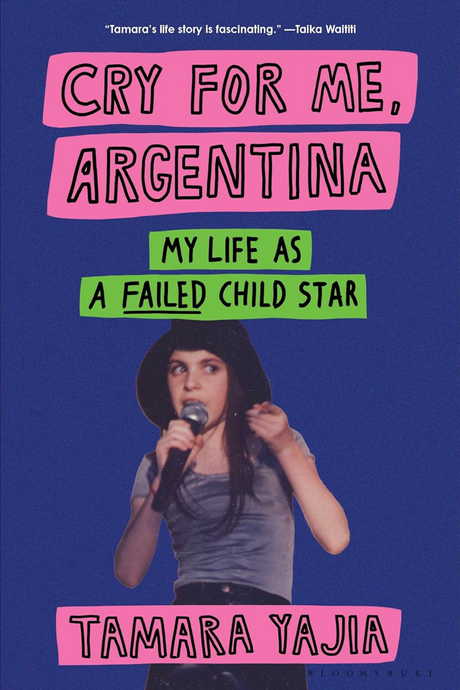

Critiquing a memoir seems tacky. You’re not assessing an artist’s work but their life, and often their childhood, when their decision-making wasn’t yet up to par. But childhood and bad decision-making are where organic comedy grows and festers, and when truly skilled writers with a knack for reflection let strangers in for an unflinching look at their blunder years, it’s a wholesome and enlightening gift. Tamara Yajia is a well-known comedy screenwriter — see This Fool, Funny or Die, and this very book, which originated as a TV pilot — whose prose ranks among the best humorous memoirists. With a mocking appreciation for her overbearing family and caustic wit for her younger self, Yajia warmly works from the thesis that kids are extraordinarily weird, scary, and kind-of-dumb creatures who really don’t know any better. In the late 1980s and early ’90s, Yajia experienced much personal upheaval and rolled with it, moving between Argentina and California a couple of times. She taps into what could be a universal feeling that childhood feels big and eventful when you’re in it and don’t have a frame of reference yet. But Yajia’s youth really was a lot. She lived all over the Western Hemisphere, flirted with minor stardom, and coped with dissociative behavior and OCD. Hers is a story that needs to be read simply because she tells it so well.

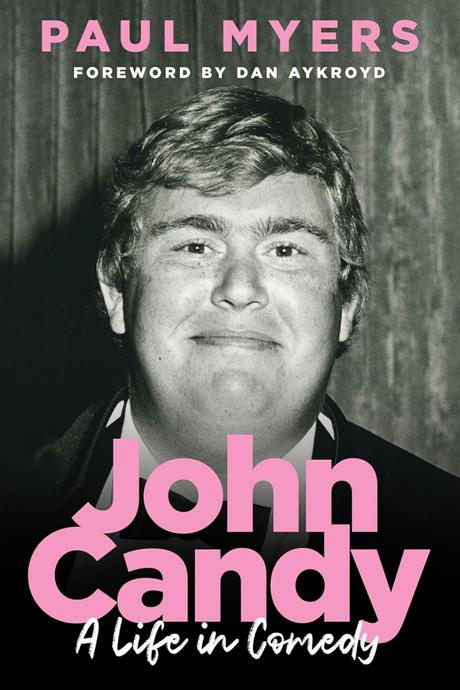

Paul Myers writes with awe, empathy, and precision about his subjects — see his books on Todd Rundgren and the Kids in the Hall — and he was the right choice to conjure a loving and deeply respectful biography on a surprisingly little-documented legend of comedy. Myers really seems to understand Candy; perhaps it’s their mutual Canadian pride, or maybe it’s because both subject and chronicler understand the comedy of empathy. In Candy’s work, comedy was about depicting humanity at its rawest and vulnerable, and his relatively brief but classics-loaded career said more about human nature than that of any other funny actor. Myers depicts Candy as like many of his characters: sweet, vulnerable, earnest, insecure yet brashly confident. It’s hard work to biograph a deceased person, but Myers is able to paint a clear portrait of Candy’s life thanks to his rich body of work as well as interviews with his many collaborators who still can’t believe their good fortune. John Candy: A Life in Comedy also partly becomes a bio of the explosive Toronto scene of the ’70s while exploring currents of profound loss and the role of fathers, both of which were major comedy themes in Candy’s era.