Photo: Les Films Impéria

“Is it a piece of shit or a load of shit?” asks Jean-Luc Godard (Guillaume Marbeck) at the end of Richard Linklater’s Nouvelle Vague, as he and his fellow filmmakers sit watching his legendary 1960 feature directing debut Breathless (A bout de souffle). “The year’s worst film,” echoes his writer colleague Suzanne Schiffman (Jodie Ruth-Forest). “Will never be released,” chimes in his friend and co-writer Francois Truffaut (Adrien Rouyard). “I slept through it,” adds his producer, Claude Chabrol (Antoine Besson). The scene is a callback to Nouvelle Vague’s opening scenes, in which Godard & Co. sat around mocking the 1959 release La Passe du Diable after its premiere. Now, they smile as they ding their own movie; it’s all meant at least partly in jest. But their exchange also speaks to a sly, uncomfortable truth about the moment: Neither Godard nor his colleagues are sure yet what exactly they’ve made. Linklater’s picture follows the creation of Breathless, and it’s a tribute to the revolutionary French film movement of the title, but it’s also an extremely Linklaterian movie about a group of buds just hanging out and doing stuff.

Which is somehow both a perfect and a counterintuitive way to approach Godard’s debut feature. Sixty-five years later, Breathless’s position as one of the most influential works of the 20th century in any medium is secure. While it may not have as many official accolades as Orson Welles’s debut, Citizen Kane (it never placed in the top ten of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time list, which was the source of Kane’s original rise to global recognition), Godard’s picture is probably the second-most-important first film of all time. It’s a momentous work whichever way you look at it. “There is cinema before Godard, and cinema after Godard,” Bernardo Bertolucci liked to say, comparing him to Christ — which is also to say that there was cinema before Breathless, and cinema after Breathless.

Breathless wasn’t the first French New Wave film, or even the second or third. Indeed, as Linklater’s movie makes clear, Godard himself felt he was late to the party, that his fellow Cahiers du Cinema critics and other newcomers had already made their first features and left him behind. Truffaut had astonished the 1959 Cannes Film Festival with The 400 Blows, as had Alain Resnais with the monumental Hiroshima Mon Amour. By the time Godard started rolling, Chabrol had already directed two acclaimed features and had produced Eric Rohmer’s feature debut, La Signe du Leon. So, with the New Wave well underway, why did Breathless strike such a nerve, and why does it continue to do so? “I still don’t know,” says Linklater, who researched the production intensely. “I know more about this film than anyone has a right to know. I know what lens they used on every shot. I know how many takes they did. I know what day and time they shot. We went into the archives and did all the research, and I’m even more impressed with it now. It really shouldn’t work, but it works. It’s a miracle of a movie.”

As with many aspects of Breathless, the fact that it shouldn’t work is part of the reason why it works. “Its revolution was probably in the boldness with which it was made and Godard’s audacity to scorn old traditions,” says film scholar Dudley Andrew, author and editor of numerous books about French cinema, including one on Breathless. “He was a fearful person, and yet his way of dealing with that was to be abrupt and willful.” For all the iconoclasm of the French New Wave, many of its other directors made what now feel like fairly traditional films: movies with narrative drive, character development, carefully considered performances, elegantly composed shots, and smooth cuts. That many of them eventually went mainstream shouldn’t surprise anyone. Godard, by contrast, threw story logic out the window. His film follows a young, small-time hood named Michel Poiccard (Jean-Paul Belmondo) who steals a car, accidentally shoots a cop, then spends the next few days in Paris hanging out with his American sort-of girlfriend, Patricia Franchini (Jean Seberg). Though Poiccard is ostensibly on the run, there’s no real suspense or urgency to their interactions; mostly, they just lie around the bedroom or walk around the streets and talk about random subjects as bystanders stare at them and at the camera. There is almost no continuity or inner psychology to the characters. “Godard has achieved a sort of ad-lib epic, a Joycean harangue of images in which the only real continuity is the irrational coherence of a nightmare,” wrote Time magazine upon the movie’s release.

Many New Wave pictures eventually took their place in the canon, but Breathless is one of the few that still feels like the work of a crazy person. “Other directors like Truffaut could line up their shooting schedules and obtain the freedom within that to make films that they admired,” Andrew says. “But Godard didn’t seem to want to play within the system of normal financial breakdowns and daily schedules. He did everything wrong, and it was shocking.” Most notably, Godard pioneered the use of jump cuts in the film, cutting within the same shot to compress time, disorient the viewer, and keep things moving, which gives certain scenes an odd, staccato rhythm. It’s an idea the director likely borrowed from Jean Rouch’s 1959 docu-fiction Moi, Un Noir, Andrew notes, but he adds that there was still chaos in the editing room when Godard began requesting these edits. “The word on the street was that he was breaking every rule, and people were shocked and afraid.”

It’s that rule-breaking, anything-goes attitude that defines Breathless. “It had a real ‘fuck you’ quality,” recalls director Jim McBride, who was 19 or 20 when he first saw it. McBride would, years later, direct a controversial American remake of Breathless starring Richard Gere and Valerie Kaprisky, but he says that he didn’t much like Godard’s film at first. “I was shocked and offended by its jaggedness,” he says. “When I saw it again not long after, I started to understand what it was all about and became a devoted fan.” At the time, McBride wasn’t thinking of becoming a filmmaker, but the freedom in the air announced by titles like Breathless inspired him to start taking some classes; soon he was also wrapped up in the avant-garde and cinema verité movements, and his 1967 mockumentary, David Holzman’s Diary, would become a seminal work of underground cinema. His 1983 version of Breathless, by the way, much despised by critics at the time but now prized by a growing cult of admirers, is a wonderful and deranged work, slick and sensationalistic in all the ways that Godard’s isn’t.

The early films of Truffaut and Resnais were clearly works of genius. But Godard’s Breathless was different. It’s rough around the edges, spontaneous and unserious, like something you and your friends down the street might have shot over a couple of weekends. That approachable quality is also why it probably inspired so many first-time filmmakers. If one of the legacies of the New Wave was to bring cinema off its dusty pedestal and make it feel fresh, young, and vital, then Breathless is the one title that speaks to us most clearly of the possibilities of the medium; it feels like something made by real human hands. Linklater recalls that he gave his actors a Godard quote when making his own first feature, Slacker, and which he later snuck into Nouvelle Vague: “A guy comes across Godard and asks, ‘What are you shooting?’ And he says, ‘A documentary about Belmondo and Seberg acting out a fiction.’ I remember saying that to my cast on Slacker. ‘You’re playing yourself acting out this fictional situation.’ I didn’t have a traditional script on that film. I just had notes, and I remember thinking, Oh, that’s one way to work.”

Among Godard aficionados, Breathless certainly has a special place, but their favorites tend to be other works, such as Contempt (my choice, along with the later Passion) or Vivre Sa Vie or Week-end. Meanwhile, Pierrot le Fou is the only one of his pictures that ever came close to breaking the Sight & Sound Top Ten, having been a runner-up in 1972. In some ways, Breathless isn’t even all that characteristic of Godard: It doesn’t star his wife and muse, Anna Karina, who would be identified so closely with his subsequent 1960s efforts, nor does it have the structural playfulness of his other films, or his pioneering use of onscreen text, or the political engagement of his later work. Maybe that’s another key to its fascination: Much as Citizen Kane’s reputation benefited from the fact that Welles never really made another movie with that level of power and polish and popular appeal (even though he did make several more masterpieces), Breathless is singular in Godard’s oeuvre. He never made another one quite like it.

Godard famously observed of Breathless that he thought he’d made Scarface but wound up making Alice in Wonderland. I’d always taken that to mean that he had set out to make a more straightforward genre film but had wound up with something wildly different. As Linklater suggests, however, Godard was purposeful in his purposelessness throughout the shoot. What he was making was in no way conventional, and he knew it. (A friend of mine who years later produced two movies for Godard was flabbergasted at the director’s way of working: Even as crews waited, Godard would sometimes not shoot anything for days simply because he didn’t know yet what he wanted to film.)

For all its thwarted genre elements, however, Breathless does retain the nervy energy of a thriller; it’s just that its thrills are totally atypical. There’s no suspense, or exciting action, or even much of a plot, and yet we sense the wild freedom of Belmondo’s existence. We don’t take the film’s story seriously, but his anarchic spirit has the ring of truth. Writing in Le Monde at the time, Jean de Baroncelli observed, “The hero of Breathless is not a criminal automaton. He is a lost kid in whom we can detect a heart and a soul — enough human depth to make us feel intimate and even sympathetic to him. His madness, his brutality, his cynicism, his sudden outbursts of tenderness and hope, that need for ‘something else’: so many exacerbated signs of the old malady of youth, of an eternal romanticism.” Compare that with Bosley Crowther’s New York Times review, in which mid-century American criticism’s foremost moralist deemed Belmondo’s character “an impudent, arrogant, sharp witted and alarmingly amoral hood. He thinks nothing more of killing a policeman or dismissing the pregnant condition of his girl than he does of pilfering the purse of an occasional sweetheart or rabbit-punching and robbing a guy in a gentlemen’s room.” These two views might seem like opposites, but they are, in fact, the same view: that of two critics seized by this character’s wild abandon, which of course is Godard’s own cinematic abandon.

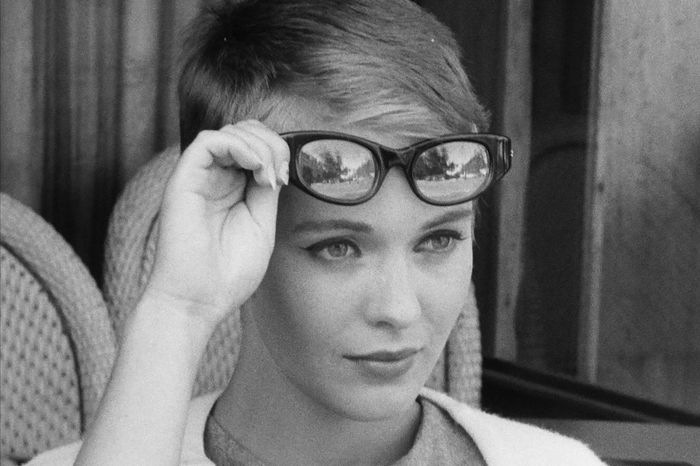

And then there’s Jean Seberg (played in Linklater’s film by a glorious Zoey Deutch). “I keep coming back to the charisma of Belmondo and Seberg,” Linklater says. “You can’t take your eyes off them.” With her crude French and slightly out-of-place mannerisms, Patricia is the young, beautiful American expatriate drawn to this wannabe gangster who idolizes Humphrey Bogart and yet seems so quintessentially French. Seberg’s performance in Breathless isn’t what one might technically call “good,” but it’s unforgettable. She struggles with the language. It’s clear that she isn’t quite sure what the hell is going on around her. You can imagine her wanting to call her agent as soon as the camera stops rolling. But just as it seems as if the film’s stylistic roughness organically gave birth to Belmondo, so too does Seberg’s transcendent awkwardness feel like it was conjured out of thin air by his charisma. We could call them the Adam and Eve of modern cinema.

The cultural give-and-take symbolized by their relationship is a kind of poisoned exchange, however. Michel Poiccard’s fascination with American movies is secretly a fascination with French movies. As Andrew has written, in the 1930s, the iconic French star Jean Gabin perfected a stoic, tough-guy style of acting in films like Le Jour Se Leve, Pepe le Moko, and Le Quai Des Brumes; that attitude then made its way over to Hollywood, where it found its fullest expression in Humphrey Bogart. In Breathless, Belmondo famously mimics Bogart’s gesture of rubbing his thumb against his lips. In so doing, he is, in a way, reclaiming the persona for France. At the end, after Seberg betrays him to the authorities and he winds up dead on the street, she coolly performs the same gesture; it’s the infamous final image of the film. Is she taking it back?

Maybe that also explains American filmmakers’ fascination with Breathless. Linklater says he was initially wary of trying to make Nouvelle Vague, because he worried the French would scoff at the idea of an American trying to make a movie about something so iconically French. “They’re kind of sick of people talking about Breathless,” he says. “They’re like, ‘There’s so much more here!’ That’s why I think they let me do it, because its legacy weighs on them a little. They’re obviously proud of the New Wave, but I think it’s some kind of Oedipal complex at this point.” Godard and his fellow Cahiers critics of the 1950s and ’60s championed American cinema, and indeed often used it as a cudgel with which to beat the French “tradition of quality” that they felt had ossified their own industry. And Breathless might be the one New Wave film to wear its American influences so proudly; it symbolizes the cross-cultural origins of this cinematic movement. No wonder it translated so well all over the world.